Nudity vs Nakedness in Photography

John Berger’s Ways of Seeing began as an investigation of art and different ways that audiences interact with art. After being released as a four-part television series in 1972, Berger followed up with a book adaptation that explored the topic brought up in the series in even more depth. However, one essay had a particularly lasting, massive influence on the way female nudes are analysed and understood by audiences. In the essay, he argues that because of societal conventions, “man’s presence is dependent upon the promise of power which he embodies” (Berger, 1973), whereas “a woman’s presence…defines what can and cannot be done to her” and that these conventions affect the way that audiences interact with images of nude females, often rendering the female subject of an image into a more submissive role.

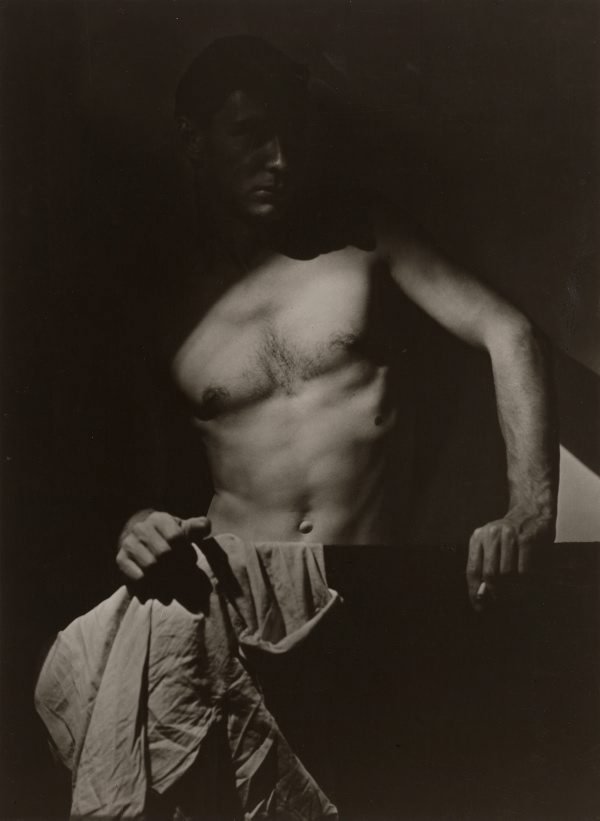

Figure 1. “Max after surfing” (1939), Olive Cotton

In the essay, Berger makes a point of outlining the difference between nudity and nakedness. He argues that to be nude is to be seen by others as an object and not as a person, whereas nakedness implies a conscious revealing of oneself. He simplifies this idea by saying “Nakedness reveals itself. Nudity is placed on display.” (Berger, 1973). Berger then moves on to point out the distinction between nude artworks and artworks of naked women, by saying that artworks of naked women often leave no room for the audience (as the subject of the photo is often a loved one), relegating them to the purely passive role of a spectator. This is the category that Olive Cotton’s 1939 picture ‘Max after surfing’ fits into. The subject of the photo, Max Dupain, was one of Cotton’s childhood friends, and they were both briefly married to each other for about two years, from 1939 to 1941. This photo was taken during the early months of their marriage, a period during which Cotton had stopped working at her studio to assume a more domestic role in their marriage. In the picture, Dupain’s face is obscured by a dark shadow, with only his bare torso and arms visible. His crumpled shirt is slung over a panel of some kind and his hand clutches a half-smoked cigarette.

Figure 2. “Derrick Cross (1983)”, Robert Mapplethorpe

In the first essay from Ways of Seeing, Berger describes an artistic image as the result of the artist’s particular perspective of a subject— “a record of how X had seen Y” (Berger, 1973) as put by Berger—and this image is a clear example of that. Robert Mapplethorpe’s work often documented the underground gay subculture that was prevalent in New York City in the 70s. However, by the 80s, his work had shifted to focus more on the nude portraits of male models, usually in a BDSM-esque scenario. This photo arose out of this era of Mapplethorpe’s work and is one of many photos published in ‘The Black Book’, a collection of photos depicting black men in erotic scenarios. Many of these images only portray segments of the body, often obscuring the subject’s face or cropping it out entirely. This led to a fair amount of criticism, such as this line from a recent New York Times retrospective of Mapplethorpe’s work, which described ‘The Black Book’s portrayal of the black body as “invasively scrutinized, sexualized, pacified, directed to sit, stand, be silent” (Cotter, 2016). Mapplethorpe’s work has played a pivotal role in the debate of censorship of art as well as federal funding for art programs especially on an occasion where one of his exhibitions was deemed to be too obscene by The Corcoran Gallery of Art and was cancelled resulting in major controversy.

The clearest similarity in both images is that they are both images where the male subject’s face is obscured, in the case of ‘Max after surfing’, by a shadow, and in the case ‘Derrick Cross’, by the turning away of Cross’s body. This has the effect of directing the subject’s attention away from the spectator, the lens of the camera, thereby forcing the audience out of the role of a participant and into the role of an onlooker. As Berger puts it, “The spectator can witness their relationship – but he can do no more: he is forced to recognize himself as the outsider he is.” (Berger, 1973).

Both photographers have also posed their subjects in such a way that their bodies have a slight bend to them, and the “masculinity” of the subjects has been emphasised to the audience, albeit in different ways. This is related to an idea proposed in the introduction to Berger’s essay, in which he discusses the impact of societal conceptions of masculinity and femininity, where he states that a man’s presence is “dependent upon the promise of power which he embodies.” (Berger, 1973). Both pictures attempt to convey a different presence of power—with Mapplethorpe’s image conveying an appreciation and promise of physical power. The most obvious difference between both images is the artist’s overall intent, which is most clearly communicated by the amount and type of nudity present in the photo. Cotton’s intention seems to be to document a loved one of hers at a particular place in time, whereas Mapplethorpe intends to celebrate and fetishize the figure of the black male.

Another core difference comes in the way that the subjects are posed for the camera, which also communicates the intention of the photo. Derrick Cross’ body is treated more like a sculpture, to be posed and manipulated to Mapplethorpe’s desire, whereas Cotton’s posing of Dupain feels less staged, and as a result, Dupain seems to be more natural and relaxed thereby making the audiences’ relation to Dupain a more empathetic human one. However, since Cross’ body is treated as more of sculpture (e.g., something to gawk at, rather than as a human being), that measure of humanity ascribed to Dupain by the audience is ripped away from Cross.

Berger’s work was revolutionary when it was first released in the 1970s and is still used as a basis of art critique to this day. However, after analysing these artworks, it becomes clear that the dividing lines between types of nude photographs do not just come in the gender of the subject, but rather in the intent of the photographer. Mapplethorpe’s intent was to fetishize (like most nude artworks of female subjects), whereas Cotton’s intent was to document her perspective of a loved one.

Bibliography

- Berger, J. (1973). Ways of Seeing. Penguin Books.

- Cotter, H. (2016, March 31). Why Mapplethorpe Still Matters. Retrieved from The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/01/arts/design/why-mapplethorpe-still-matters.html

This essay was originally written for a school assignment back in June, I just forgot that I actually had a website until today.

Tagged with: photography / school